Good health, so the saying goes, is priceless. But beyond the proverbs, the opposite is true. Medicines cost money, and the figures are rising all the time. And if that’s true at the end of the drug supply chain – the price of new drugs in the US jumped by more than 35% in 2023 – something similar is happening at the beginning too. Once again, the numbers here are clear, with the US Bureau of Labor Statistics reporting that per-patient clinical trials cost rose over fourfold between 1989 and 2011, even as the global spend is expected to reach almost $70bn by 2025.

There are plenty of ways to understand this increase in clinical trials cost, from patient recruitment to study design to operational expenditure. Whatever the cause, at any rate, the repercussions of spiralling costs are clear, not least when it comes to the sorts of projects pharma firms approve. “We are seeing biopharma clients having to cut costs and reduce the size and prioritise their drug development pipelines,” explains Dawn Anderson, a clinical trial expert at Deloitte, adding that “fewer clinical trials” could ultimately be green-lit.

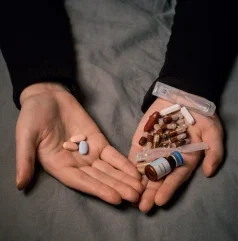

Once you factor in the impact of expensive trials on patients themselves, it becomes obvious that soaring trial costs can have severe real-world consequences. Even so, the situation is far from hopeless. Between limiting waste via digitalised drug sourcing, and securing dynamic third-party vendors, there’s plenty trial conveners can do to keep prices down. That is, of course, if they get to grips with the technology needed to bolster efficiencies – and tackle the data security issues that follow close behind.

Paying the price

Beyond the headline statistics, experts have been flagging rising clinical trials cost for years. If Anderson is one example here, Salman Shah is another. A clinical research expert at EY, he suggests that “if you look at the curve” clinical trials have been getting more expensive for around two decades. Perhaps inevitably, meanwhile, Shah warns that the pandemic has exacerbated the situation too. As he puts it: “The installation costs – labour costs – played a significant role in recent years.”

That’s not hard to appreciate: with lockdowns and social distancing, trial conveners had to rush to embrace new trial models, which in the short term is bound to raise expenses. In truth, though, the current trend for pricey trials runs much deeper. That plausibly begins with personnel. Whether due to residual pandemic fears, regulatory hurdles, or else the need to secure subjects from specific populations, Anderson says that patient recruitment can “often be a lengthy and costly process”. Certainly, statistics support this claim, with work by Parexel finding that 80% of trials are stymied by a lack of manpower. That’s echoed, Anderson continues, by the increased sophistication of studies themselves. For one thing, personalised and sensitive treatments like cell therapy are bigger-budget drugs than generic alternatives. For another, wearables and connected devices, though inevitable from a data perspective, are necessarily pricey too.

Ironically, though, arguably the biggest pressure point for trial accountants isn’t directly in their control. There are two ways of thinking about this. One involves comparator drugs, the medicines against which a new medicine is tested. As so often, the research here speaks for itself, with the global comparator sourcing market predicted to hit the $1.3bn mark by 2031. And if that means conveners need to take out their wallets ever more frequently, it can be just painful to manufacture investigational products (IPs) themselves, let alone ship them to the patients who need them.

As Anderson’s warning about scaled-back trials implies, moreover, the impact of unequal balance sheets is increasingly shaping clinics around the world. From a medical perspective, that’s necessarily most worrisome for patients. “A lot of these therapies are usually last-resort for patients – especially in cancer,” emphasises Shah. “And if we can get it to them, there’s hope to elongate their lives, which has a huge meaning behind it.” And though rather less important from a humanitarian perspective, fewer drugs to sell naturally feeds back into the finances of pharma companies too, with delays of over a month costing $8m each and every day.

Fewer costs, more benefits

How can sector insiders begin to make trials more economical? Given how vast the outlay can be, it’s unsurprising that many companies are focusing on comparators. In the first instance, that means honing third-party relationships, ultimately making crucial drugs cheaper to source. A good example involves AstraZeneca, which partners with Essex-based ADAllen to secure test drugs quickly and efficiently. Across the Channel, at its Centre of Excellence in the Swiss town of Luzern, Merck has a dedicated team to pick comparator vendors – as well as manage supply chains and understand trial timelines.

“We are seeing biopharma clients having to cut costs and reduce the size and prioritise their drug development pipelines.”

Dawn Anderson

Of course, it’s all well and good relying on external expertise here. But as Anderson stresses, that doesn’t solve the issue of getting comparators (and IPs) to where they’re needed, something that in practice can be achieved through the immense power of technology. As she puts it: “We are seeing a focus on driving automation solution and predictive analytics to be able to improve how you decide when to ship the right amount of investigational drug and comparator to the correct clinical trials sites at the right time, so that drug is available for patients, but not sitting idle at a site that is not recruiting well.”

“A lot of these therapies are usually last-resort for patients – especially in cancer. And if we can get it to them, there’s hope to elongate their lives, which has a huge meaning behind it.”

Salman Shah

It goes without saying, meanwhile, that big data and the like can also ensure pharma conveners choose the most efficient (and ultimately the cheapest) supplier for the job, even as technology can lower clinical trials cost in other ways too. From generative AI to machine learning, Shah explains that automation can help pharma companies “fail fast” – quickly abandoning trials that aren’t bringing results, cutting their losses and not ploughing resources into pointless ventures. Considering the median start-up time for oncology trials is 33 weeks, that’s sure to make the accountants happy, particularly when AI can also pinpoint exactly the sort of subject conveners should recruit.

Tech trouble

All the same, technology probably isn’t a panacea. Think about it like this: if ones-and-zeros can quickly tell pharma staff who to approach, there’s no guarantee that subjects will actually agree to undergo tests. With that in mind, no wonder some industry experts are pushing to pay people better, especially when remuneration remains so inconsistent. That’s echoed by other common sense tactics, for example, liaising with several comparator suppliers at once, ensuring that there’ll always be drugs to spare if the vagaries of global supply chains cause problems elsewhere.

$1.3bn

The predicted size of the global comparator drug sourcing market by 2031.

Growth Market Reports

And if that makes sense from a statistical perspective – industry wisdom suggests that companies should aim for ‘overage’ of 40–50% – Shah speaks to the broader benefits of keeping different parties happy. “I think,” he says, “we need – as a continuum of the entities, or the players, or the stakeholders involved – to have better relationships between them, which will allow us to be much faster and improve that trust process.”

Fair enough: with 58% of pharma suppliers lacking proper visibility into their supply chains, there’s clearly room to bring people round the table. Not that relationship management is the only potential stumbling block here. Let’s return, to give one example, to the question of technology. It obviously has a lot to offer financially – but digitalisation inevitably dovetails with privacy worries too. “There is still a lot of concern around data privacy and security around use of patient data in clinical research,” Anderson says, noting that patients may not be willing to share their information. From there, the Deloitte expert continues, is the need to abide by privacy rules, no easy task when regulations vary across borders and the trials are under way in literally hundreds of countries.

Once again, that arguably hints at the human aspect of clinical trials, with conveners under increasing pressure to reassure patients that their data will be used ethically. There’s rising evidence, in fact, that some of the world’s biggest pharma companies are moving in just that direction. At J&J, for instance, staff explicitly commit to ensuring data integrity, while Pfizer emphasises it’ll return trial data to patients a year after the trial ends. Between that and the digital wizardry, Anderson is optimistic about getting clinical trials cost down over the years ahead – at least once the technology fully matures. Especially as more conveners pull data directly from medical records of patients, Anderson adds the underlying costs could decline “significantly” in future. Given how important keeping prices down is to patients and pharma firms alike, you have to hope she’s right.