A breakthrough in fully synthesising the anti-cancer molecule halichondrin could hold the potential to find a cure for the disease, according to an industry analyst.

A joint project between Japanese pharmaceutical company Eisai and Harvard University found that the molecule can be manufactured in a lab, and on a large scale, for clinical testing.

Previously, it had only been sourced by Japanese scientists Yoshimasa Hirata and Daisuke Uemura from sea sponges, with the lack of availability preventing clinical testing on a meaningful scale.

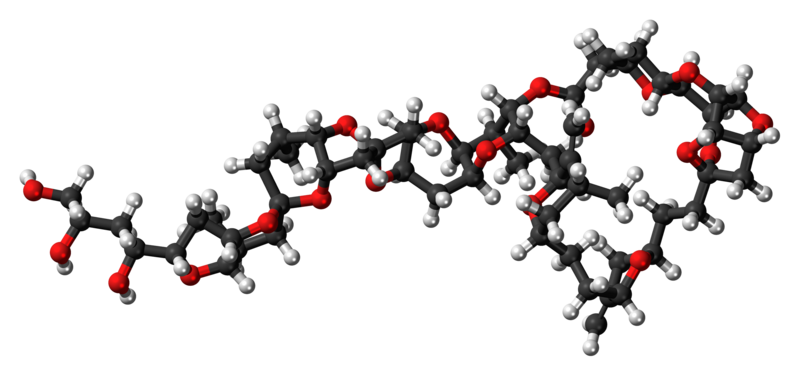

However, scientists at Harvard’s Kishi lab have been able to fully replicate halichondrin’s unique structure — with Eisai’s chief discovery officer in oncology Dr Takashi Owa highlighting how this was particularly difficult because there are 4.2 billion ways it can be oriented.

This finding is the result of 30 years’ research into halichondrin, which reportedly exhibited strong anti-cancer activity in mice, fuelling hope that it could be developed into a powerful new class of cancer therapeutics.

Mice share more than 95% of DNA with humans, leaving scientists hopeful this can be replicated in humans to treat cancer in the future.

The Kishi Lab has now achieved total synthesis of halichondrin at scale, producing 11.5g of a drug candidate referred to as E7130 with 99.81% purity — the measurement of the quantity of a drug substance where only the prevalent component, in this case halichondrin, is present.

Industry analyst GlobalData says Eisai is now moving fast to translate this discovery into a new clinical product.

Trials assessing E7130’s effectiveness against solid tumours have been ongoing since February 2018, and the company also plans to incorporate the new candidate into two studies of eribulin, a drug used to treat breast cancer and a type of cancer that originates in fat cells known as liposarcoma.

What is halichondrin and why do scientists think it could provide a cure for cancer?

Halichondrin B is a naturally occurring molecule that scientists have been able to isolate from a species of marine sponge called Halichondria okadai.

The complex molecule is a highly potent anti-tumour agent, meaning it inhibits their formation and growth by killing the rapidly dividing cancer cells.

Specifically, it does this by targeting the tumour micro-environment (TME) in a unique fashion by increasing the number of CD31-positive endothelial cells within a tumour and decreasing the number of cancerous smooth muscle actin-positive fibroblasts — the cells that create a structural framework for tumours.

Dr Owa says: “Both of these effects may be connected with the amelioration of the TME, resulting in the enhancement of combination drugs’ anti-tumour activity in pre-clinical animal models.

“Based on these observations, we would expect clinical activity of E7130 not only in monotherapy but also in combination with other oncology drugs, including immuno-oncology agents.

“Given the fact that the immunosuppressive tumour microenvironment is one of the key resistant factors for the currently available immuno-oncology therapies, we would expect the TME-ameliorative effect of E7130 may contribute to a cure for cancer.”